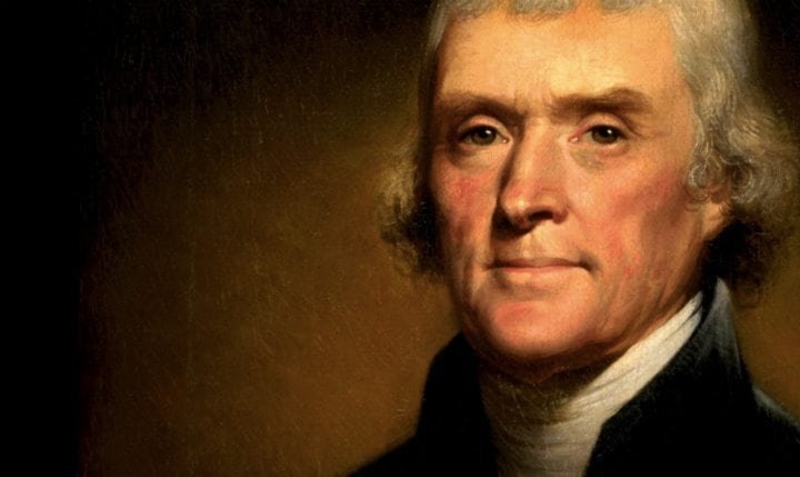

Translated from Italian as “Little Mountain”, is Monticello, third U.S President Thomas Jefferson’s plantation estate. Acquired by Jefferson in 1777, the renowned Founding Father’s property near Charlottesville Virginia, as well as its workers, to this day, hold a significant place in U.S history. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which has preserved, and maintains the 5,000-acre property, notes that “to understand Jefferson, one must understand Monticello; it can be seen as his autobiographical statement.”

The iconic property is a national landmark, and has been the subject of quite some interest by American, and international scholars. Whilst there is a plethora of documentation regarding Jefferson’s primary home, there has been a push by academia and archaeologists alike to delve deeper into the original use of the property and the activities which took place within its grounds. The initiative taken was not for nothing however; a discovery was made which has left historians astounded. Not only in regard to the livelihoods of the people who lived there, but in regard to what it meant for the history of the United States. Let’s take a look at what they found!

A President’s Plantation

As Thomas Jefferson’s primary residence, Monticello was his home before he moved to the White House in 1801. Today, the estate is preserved by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Open to the public, it is regarded as a historical landmark. Construction of the expansive estate commenced in 1768, with its renowned sprawling grounds well-documented and well-known.

Fun fact; an image of the plantation’s main house is ingrained on the flip-side of the U.S. nickel! Intense research and constant study of the property had not yielded a find quite as fruitful as the one recently uncovered by historians. A mystery which had baffled historians and political scholars for the years seemed to be hiding in plain sight.

The Controversy Surrounding Monticello

Born in 1743, Jefferson began building Monticello at 26-years old. Having inherited the land from his father the initial purpose for the land was to cultivate wheat and tobacco. Charlottesville, named after British Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, is an area which is characterised by hot, humid summers and mild winters, which made it suitable for growing these crops. Such as is the case with many family-held plantations in America, Monticello is not alone in having its own dark past.

Jefferson used free workers along with servants and enslaved labourers to construct the plantation house, however he also had hundreds of slaves working and living at Monticello. Whilst he consistently spoke out against the chains of slavery, and worked to end the practice, he had a secret of his own. Many individuals to this day find his dark secret a difficult pill to swallow, however the discovery made in 2017 by a group of archaeologists creates a case for Jefferson, shedding light on a matter which was previously unresolved.

A Complicated Legacy

The principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson is regarded as one of the most prominent figures in American history. One of the U.S’ visionary Founding Fathers, he, somewhat ironically penned the famous line “All men are created equal.

Ironic why you ask? Jefferson, despite the airs and graces he upheld, simultaneously kept 600 African-American slaves for the duration of his adult life. As such he left a legacy which reflected his duality; his political life and his personal life. The discovery in 2017 during an excavation on the estate contributes to history’s understanding and opinion of Jefferson, causing many to re-evaluate his contribution.

An Enigmatic Figure

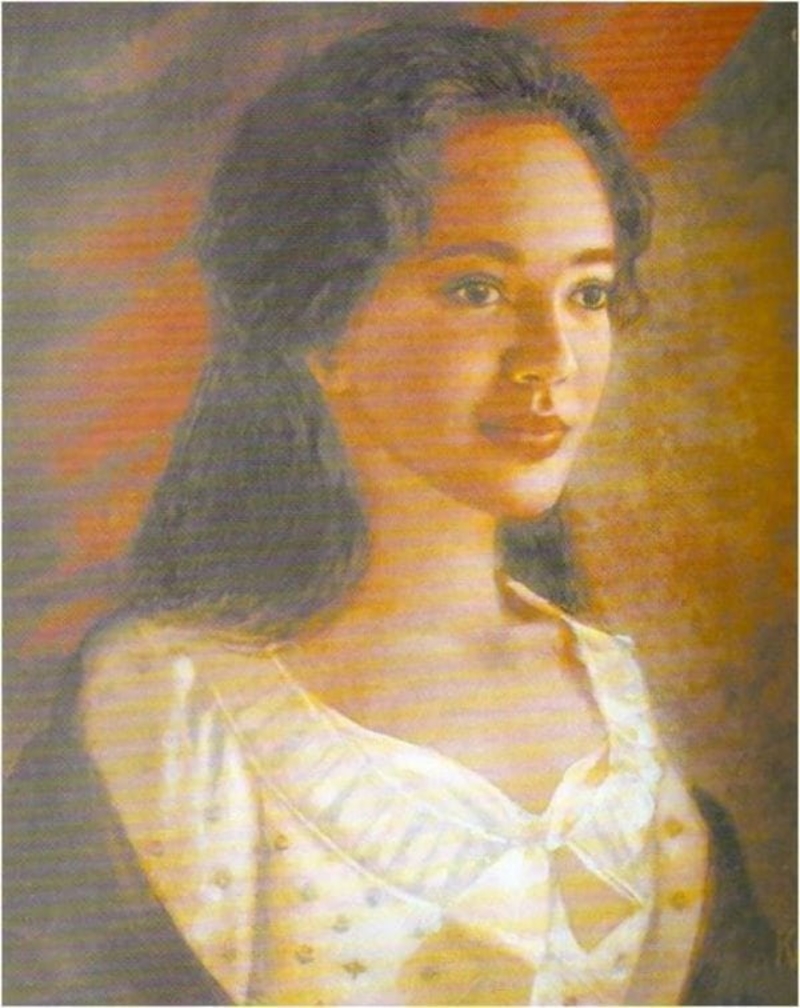

Among the 600 slaves is a key figure in the Jefferson mystery. Enter Sally Hemings. For the most part, she remains a puzzling figure, however historians cannot discount her involvement in Jefferson’s life.

Naturally, her story piqued the interest of historians, and has continued to do so for over a century. Almost 200 years after her death, the discovery made brought some new insights into who she was and the events which took place during her time at Monticello estate.

Who Was Sally Hemings?

Born in 1773 to a planter and slave trader named John Wayles, who was also the father of Martha Jefferson, Sally was the half-sister of Thomas Jefferson’s wife. As a child, Sally, her siblings and mother came into Martha’s possession as part of her inheritance from her father. An enslaved woman of mixed race, she held an important place in Jefferson’s life. Owned by Jefferson, the historical consensus is that Hemings was the mother of his children. Due to legalities, the children she bore were considered slaves.

The historical question of whether Jefferson did father Hemings’ children is the subject of what is known as the Jefferson-Hemings controversy. Much investigation, and historic analysis of DNA found a match between the Jefferson men and a descendant of Hemings’ youngest son, Eston. It has since been alleged that Jefferson was the father of all five of her children. We’re scratching our heads; which version of events is true?

Before She Was a Subject of National Intrigue

The youngest of 6 siblings, and 25 years younger than her half-sister Martha, Hemings and her siblings grew up at Monticello. Trained and put to work as servants, the children were “spared” as they held positions which were considered better than the conditions of others, such as the labourers in the fields.

During her youth she was quite the plain Jane, but years later, it was her destiny to become a figure who was scrutinised, eventually becoming a household name. She would be described as the former President’s “mistress” however she was not even that; she was his property. Her story is not one of glamour and pomp; rather it is the life of a slave whose wellbeing was betwixt with that of her owner.

A Trail of Clues

Hemings unfortunately did not know much life outside of being a slave; she was kept until Jefferson’s death in 1826. Whilst she lived her final years freely, the details of her time at Monticello are largely unknown. However, the keen eyes and scouring of documentation by scholars and historians unveiled a series of clues which has thus led to a better understanding of Hemings’ importance and historical significance.

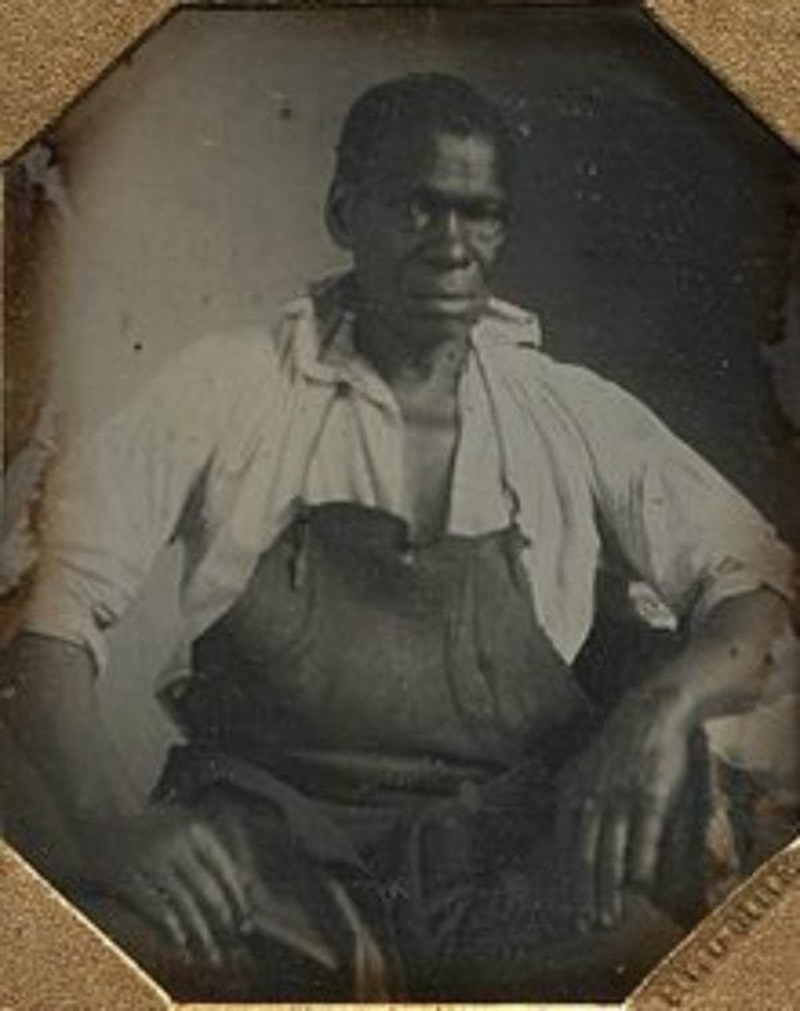

At this stage, we’re wondering what it was about Hemings that caught Jefferson’s eye; was it her lovely face, her physique, her pleasant character? One of the only existing documents which describes her appearance, which was written by the blacksmith Isaac Granger Jefferson gives us partial clues. According to his memoirs, Hemings was “mighty near white…very handsome, long straight hair down her back.” Whilst it seems apparent as to why Hemings took Jefferson’s fancy from this description, there are a few crucial elements still missing in the Hemings-Jefferson puzzle.

Painting a Picture

Being a slave, it was highly inappropriate for portraits to be taken, however historians have constructed an image of her based on the descriptions documented. According to Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, she was “light coloured and decidedly good looking.” As far as her role in the plantation, historians have noted her duties included working as a seamstress as well as a chambermaid.

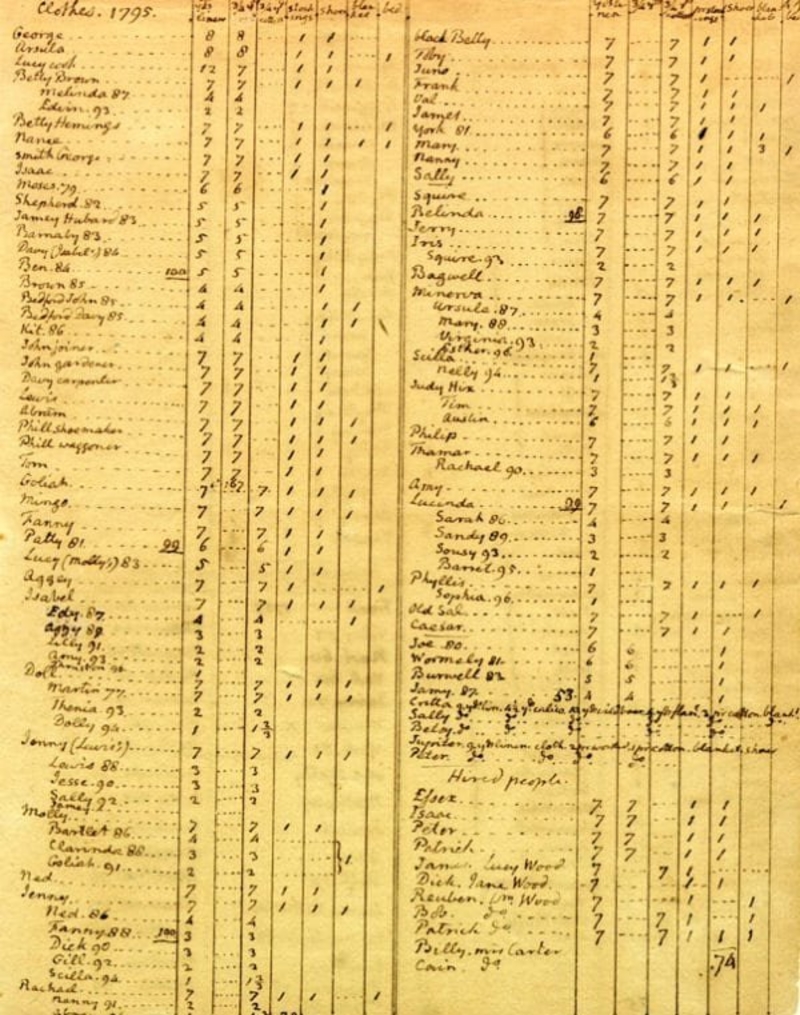

Perhaps surprisingly, the diligent and meticulous Jefferson, whilst keeping detailed ledgers of finances and births in his records of Monticello, left not a shred of documentation on Hemings. Whilst her face would be forever etched into Jefferson’s memory, and may show in the faces of her children, it will forever be a mystery as to what Sally actually looked like.

The French Connection

Jefferson widowed at 39 years of age. Two years later, in 1784, he took his eldest daughter Martha to Paris. He then sent for his youngest daughter, the 9-year-old Mary, who was accompanied by the 15 year old Hemings. The future President served as the U.S. envoy to France; it was during these two years that Sally’s life was to change forever. Hemings’ brother James also accompanied the Jefferson’s to Europe as their personal chef.

In France at the time, slavery was prohibited, and both Sally and her brother could have petitioned for freedom and lived in France as a free person. If she returned to Virginia with Jefferson, it would be as a slave. She agreed to return to the United States, for a reason which is both shocking yet also in the best interests of Sally’s secret.

What Happens in Paris, Doesn’t Stay in Paris

Ah Paris…the city of love. Not the city of teenage pregnancy. It was in Paris that historians agree Jefferson began a sexual relationship with the young Hemings. He was in his mid-40s, and she was barely 16. It was at this time that, according to Hemings’ son Madison, Hemings became pregnant by Jefferson. The pair returned to the U.S. in 1789, and it seems that the child she bore was not the only one that would call Jefferson “father.”

Sally went on to have six children following her return from Europe, and reports from the time suggest that they were indeed all Jefferson’s due to the strong features and strong resemblance to their father. This relationship was kept extremely discreet; any sort of relations with a slave would be scandalous, particularly against the name of a man running for the position of President. It was not until over 20 years later that the facts would come to light, and the controversy would come to the fore.

Unproven Allegations

Come the spring of 1802. After 20 years, the “Jefferson-Hemings controversy” was born. One of Jefferson’s opponents, James T. Callender, published a report which smeared his reputation, after reports of several light-skinned slaves at the Monticello plantation. Jefferson never denied the allegation publicly, nor did he divulge the father of Hemings’ children in his detailed “Farm Book.” However, his family attempted to hush the story in later years, denying Jefferson’s hand in the controversy.

The children he allegedly fathered who survived into adulthood were freed once they were of age, which nigh confirmed the rumours that he was indeed their biological father. His family once again, as well as historians to this day, vehemently deny the paternity allegations. It was not until 150 years later, when historians began reanalysing the evidence, that a new piece of information would subvert the accepted truth.

After 150 Years of Uncertainty…

American historian Annette Gordon-Reed published a book in 1997 which analysed the Jefferson-Hemings controversy, and the flaws in the “accepted truth.” Her scrutiny of the historiography of the saga found that 19th century historians had merely accepted assumptions without further investigation. They dismissed the Hemings family’s testimony as “oral history”, deeming Jefferson’s family testimony as the only truth. The story which had been propagated by the Jefferson’s was that the father of Hemings’ children was Peter Carr. However, the 1998 DNA analysis showed there was no match between the Carr line, and the Hemings’ descendant who was tested.

The breakthrough you ask? That there was a match between the Jefferson male line and Eston Hemings’ descendant! Eston was Sally’s youngest son, and his DNA was the link which shed light on the astounding controversy, proving that the Carr story was a fabrication, and, revealing the absolute truth that Thomas Jefferson did indeed have intimate relations with a slave. Not just once, either. Two decades later, archaeologists today were to discover a long-hidden secret that provided an even bigger revelation of her life.

A Monumental Discovery

For over 90 years, Monticello has been lovingly maintained and restored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. It is frequently subject to the probing of historians, archaeologists and the general public alike. However, in 2017, said probing was fruitful. During a dig, archaeologists, in their restoration efforts, discovered a piece of the puzzle which had eluded them for quite some time. They discovered the concealed living quarters of Sally Hemings! Their excavation was initially proposing to uncover the original layout of the Monticello plantation’s Southern Wing, however they definitely stumbled across something much more exciting.

Despite several decades’ worth of work, the room had remained untouched and undiscovered. Something which had slipped through the fingers of social scientists had finally made itself known, and was a discovery which set the nation aflame once again with the headlines of the Jefferson-Hemings controversy.

Hidden in Time

It was extremely fortunate that the archaeological team came across the room, particularly owing to the fact that the southern Pavilion of the estate had been subject to a large number of changes, both during and after Jefferson’s lifetime. A museum had been constructed and many people had passed on through (and above) the hidden living quarters. You may think; how did a whole room just disappear?

Well, in 1941, the installation of a modern bathroom concealed the room, completely covering any trace of an opening. Again in the 1960s, the bathroom underwent a renovation to accommodate the increasing number of guests at Monticello. Even still, the changes did not reveal Hemings’ long-lost living quarters. The point which alerted archaeologists, and motivated them to dig deeper (literally), came to them in a most surprising fashion.

A Historic Hint

It was during the analysis of the history of Monticello that historians came across a surviving document written by one of Thomas Jefferson’s grandsons. The source revealed that Sally Hemings’ room was in fact located in the South Wing of the former main house. Whilst historians were sceptical at first, and knew not to take the word as gospel, it did raise questions which led them to consider the modern restroom addition, and subsequently, to dig.

With each turn in this tale, it seems that archaeologists and historians were to uncover new artifacts and missing clues which piece together the history of Monticello, and of its inhabitants. During the excavation, historians unearthed a number of relics, all pointing to one thing.

Sally’s Room

Taking heed of Jefferson’s grandson’s clues, the archaeologists proceeded to demolish the men’s bathrooms, sieving the dirt for fragments and clues to the mystery. Their digging was not for nothing; they eventually discovered Sally Hemings’ 14-foot living quarters. Among their discoveries were original brick floors from the early 1800s, a brick hearth and fireplace, as well as a fixture which was a suitable structure to hold a stove.

However, the point which really flabbergasted archaeologists was the room’s vicinity to Jefferson’s private bedroom. It was located directly adjacent. It seems that there was more truth to the controversy than initially imagined, a dark secret which, after over 170 years, was finally to see the light.

What It Means

Historians and archaeologists alike see the proximity of Hemings’ room to that of Jefferson’s as a tell-tale sign that he indeed was the father of her children. The discovery of the room, as well as the results discovered in the DNA almost certainly provide solid proof of their intimate relationship. What this meant was that a man who supposedly upheld justice in his position as President, was just as corrupt and hid secrets as any other man.

Fraser Neiman, director of archaeology at Monticello remarked “this room is a real connection to the past.” He went on to say that as they dug deeper, “we are uncovering and discovering and we’re finding many, many artefacts.” The room did not only uncover their secret, but also filled in the gaps for many historians, answering questions which had been asked time and time again, yet not answered.

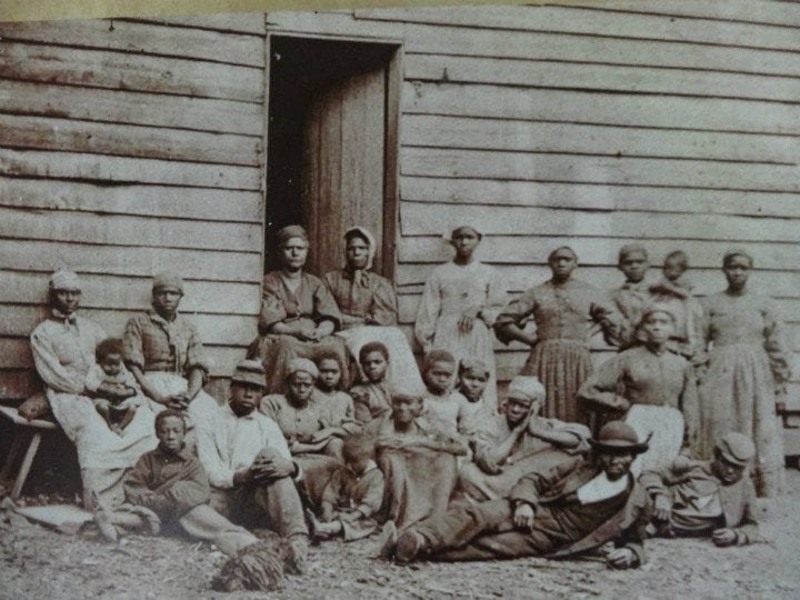

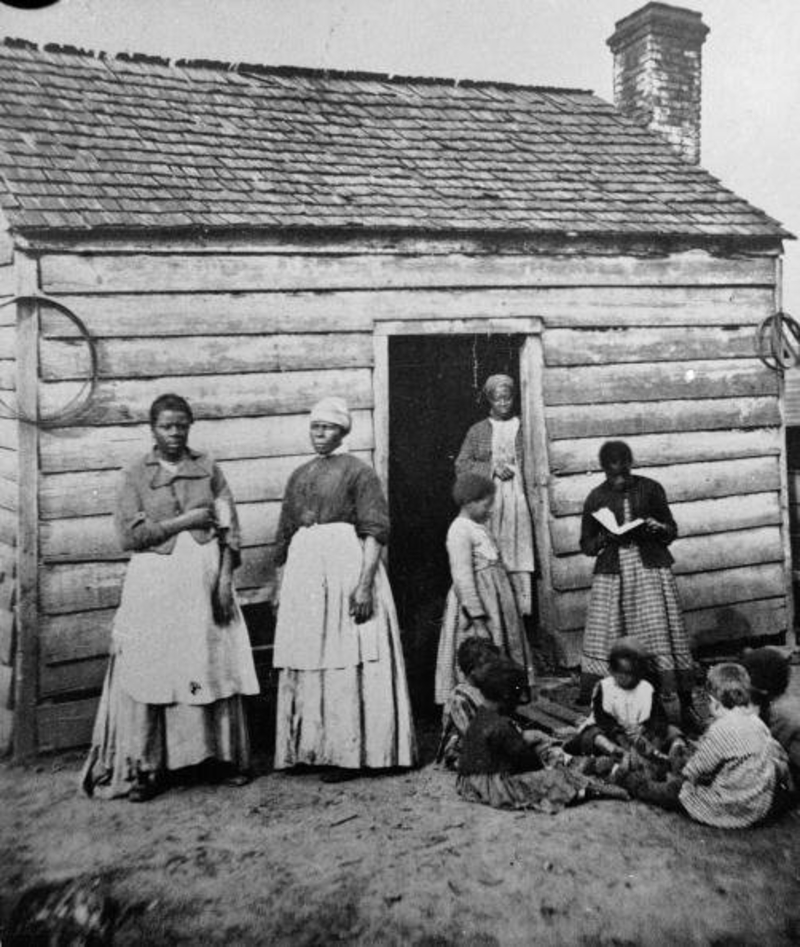

How Enslaved People Were Living

The room also highlighted the difference between the Hemings’ lives as slaves, versus that of the others. Gardiner Hallock, director of the restoration for Jefferson’s home, noted that “the discovery gives us a sense of how enslaved people were living. Some of Sally’s children may have been born in this room.” “It is important because it shows Sally as a human being- a mother, daughter and sister – and brings out the relationships in her life.”

Whilst the paradox of liberty rests with Jefferson, in that a man who cried out for the freedom of all not only kept slaves but kept one as a sexual slave. Not the most flattering secret to expose, particularly one regarding a U.S. President! It is speculated that Sally’s decision to return from Paris was owing to the fact that Jefferson promised the children she bore would be free once they came of age (21 years old). Perhaps not surprisingly, the Hemings were the only family that Jefferson freed among the slaves he kept (aside from three very lucky others).

A Window into the Past?

Uncovering Sally Hemings’ room also revealed that she enjoyed a standard of living well above that of the other slaves who lived at Monticello. Regardless, she was still a slave, and was treated thus, though there were some indicators which shed light on her own living conditions. Historians note that Hemings’ room was dark and dingy, with no natural light allowed in; there were no windows whatsoever, so the conditions would have been uncomfortable.

Some historians have mentioned the possibility that building the bathroom above her quarters was calculated; it was an attempt to cover up Sally and her secret, as it was considered a great insult, not only to Jefferson’s legacy, but to her own. However, following her death, her story was to be known to all.

Revealing the Truth

Following its discovery, historians and the committee of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation sought to restore Sally Hemings’ room for public display, with its expected open date to be during 2018. The space is designed to exhibit with furniture of the period as well as artefacts excavated on the property; such pieces include fine ceramics and bone toothbrushes!

Where previously the secrets of the estate were kept under lock and key, the $35-million Mountaintop Project at Monticello has made a bold effort to create more transparency; to tell the stories of both the free and enslaved people who inhabited the estate. In recent years, tours have been offered which focus solely on the Hemings family, with a reception which has been overwhelmingly positive.

A First

Spokeswoman for Monticello, Mia Magruder Damman notes that “for the first time at Monticello, we have a physical space dedicated to Sally Hemings and her life.” The significance of this discovery, and the ability to pay respect to her life is extraordinary, as it “connects the entire African-American arch at Monticello.” The discovery did three things; it answered questions, it clarified rumours, and gave insight to the daily activities of Monticello, as well as the human interactions there.

The estate’s curators are now working around the clock to more solidly incorporate her life, rightfully, into Jefferson’s story, and dismiss the notions that she was merely his mistress; his “concubine.” But we are not quite finished there; there is more to the story, and these other facts hold even greater significance.

Outside of the Mystery

Monticello estate is seemingly finished with avoiding Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings, with a new exhibit shedding light on the realities of slavery, as well as the truth behind Hemings. The discovery of Hemings’ room also allowed for the public to see the real, human side. Niya Bates, historian, remarked that the room would “portray her outside of the mystery” – no longer a topic of debate and speculation, but as the living, breathing woman she was.

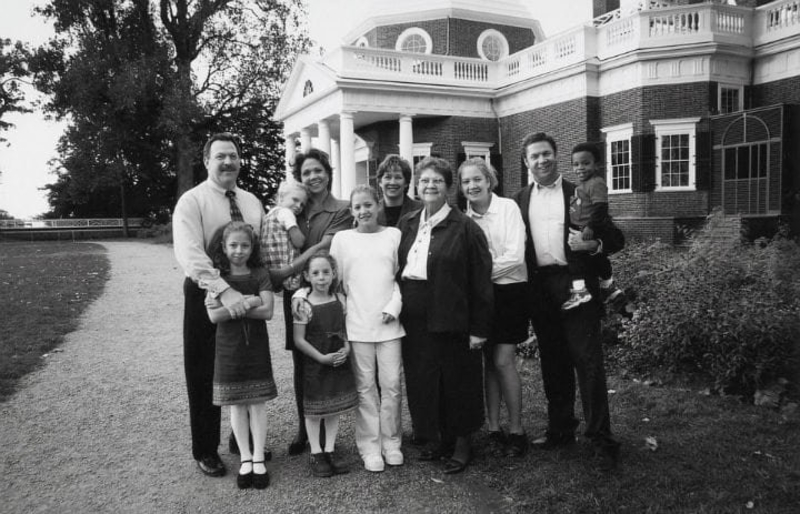

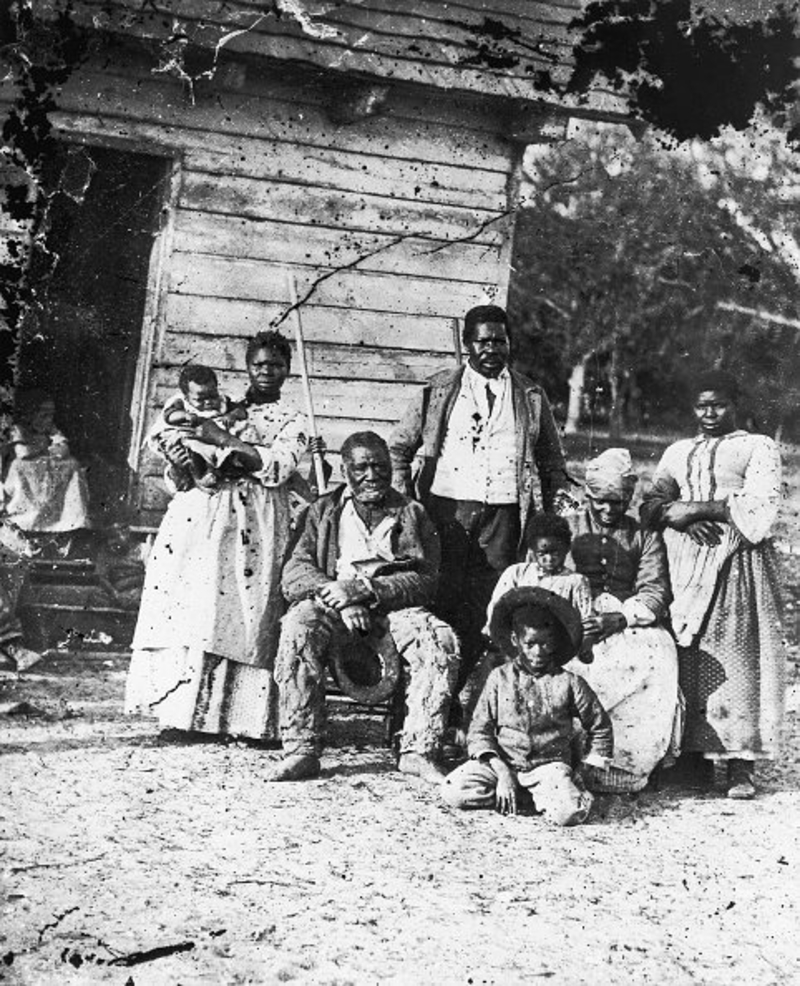

The exhibit seeks to bring life to a woman who was constantly linked to the drama of Jefferson’s life, not to mention terrible rumours and scandalous gossip. “She was a mother, a sister, an ancestor for her descendants (pictured), and [the room’s presentation] will really just shape her as a person and give her a presence outside of the wonder of their relationship,” Bates stated. Before the room was discovered, Sally’s name was never mentioned, and tours skimmed briefly over Jefferson’s love life, merely noting that he widowed a relatively young man.

Remembering Sally’s Name

With its newfound focus on the realities for the majority of the people who lived and worked there; not just the wealthy owners, Monticello’s change of course departs from the original portrayal towards the public. Retired historian Lucia “Cinder” Stanton began working at Monticello estate in 1968, and recalls that during her time there, Sally’s name was never mentioned; it was Monticello’s dirty little secret.

Back in the 60s it would have been scandalous to unveil such a secret, even if there were rumours whirring around; as such, little was said about the Hemings family in its entirety. It was not until the 250th anniversary of Jefferson’s birthday in 1993 that the tours began to include stories of the slaves who worked and lived on the estate. Despite this giant leap forward in uncovering the truth of the livelihoods of those who lived there, it would take many more years for another fact to come to light. This fact would bring the descendants (pictured) of the slaves to visit the property their ancestors once called home.

Remembering Mulberry Row

Enter Mulberry Row, the dynamic, industrial hub of Jefferson’s grand enterprise. This famed street was the centre of work and domestic life for many people. Monticello unveiled the restoration of Mulberry Row in 2015, displaying a series of reconstructions of dwellings from the plantation street.

Between 1770 and 1831, when Monticello was sold, the row comprised 20 buildings. The important unveiling welcomed over 100 descendants of slave families, with an emotional tree-planting memorial ceremony taking place in their ancestors’ honour. This was only the beginning of commemorative efforts, as the significance of the lives of these people grew, as well as their connection to their modern successors.

A More Comprehensive Account

Once the room was discovered, it opened the floodgates for a much-needed re-telling of the Monticello estate’s history. Just as the tide had turned with Mulberry Row, and for once, recounting the story of the majority who lived and worked there, so it was for Sally Hemings. Curators of the estate decided to incorporate her room and life into a fuller account of Monticello and its people; not just its wealthy, well-known owners.

The breakthrough has acknowledged a dark, yet important part of history which was necessary for Americans to be aware of, however it also has had a negative impact on some. Hemings’ distant relatives hold a mixed response about their ancestor’s legacy, and particularly her dalliance with American president Thomas Jefferson.

A Descendant’s View

Whilst the discovery of Hemings’ room gave closure to some, it also gave answers which were less than satisfactory. Gayle Jessup White, Sally Hemings’ distance niece notes that “as an African-American descendant, I have mixed feelings – Thomas Jefferson was a slaveholder.” White, who works as Monticello’s Community Engagement Officer, is within her rights to feel uneasy, what with her father, the former U.S. president, and her mother, a lowly slave. The social differences were so great that it leads one to believe that Jefferson conveniently held Hemings as property and did not bother to think of the consequences of his desires.

White, as an African-American woman appreciates the work of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, as, “for too long our history has been ignored.” Indeed, the discovery shed light on the real truth behind Monticello, and that this sort of arrangement may have been more common spread than initially believed. “Some people still don’t want to admit that the Civil War was fought over slavery. We need to face history head-on and face the blemish of slavery and that’s what we’re doing at Monticello.” White is not alone, and, joined by her colleagues they seek to unveil more truths about the property and its history.

Mixed Feelings

What with its dark past, Monticello was never accepted by the majority of the local African-American community, owing to Jefferson’s mixed messages regarding slavery. On one hand, he was a champion of justice, and wished to abolish it, however kept 600 of his own. “I find that some people are receptive to the message and some are resistant,” she said. “But our message is that we want the under-served communities and communities of colour to become partners with us.”

Whilst White acknowledges that there is much more work to be done with spreading the stories of their ancestors, “anecdotally we have seen an uptick in African-Americans visiting Monticello, so I know we’re making progress.” It is yet to be seen if the community will finally embrace Monticello, however, it cannot be doubted that it is undeniably a part of the history of the African-American people.

Remaining Questions

Despite the answers provided by the finding of Hemings’ room, it still remains that there are a number of questions which still require further enquiry. Despite the great historical analysis of Monticello, of its records and documents regarding the estate, the history of the former plantation remains mysterious in its own ways.

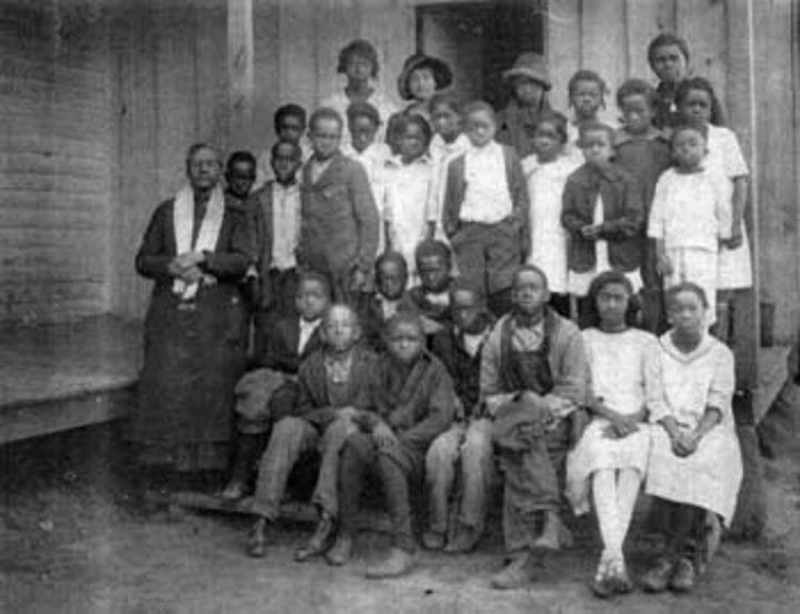

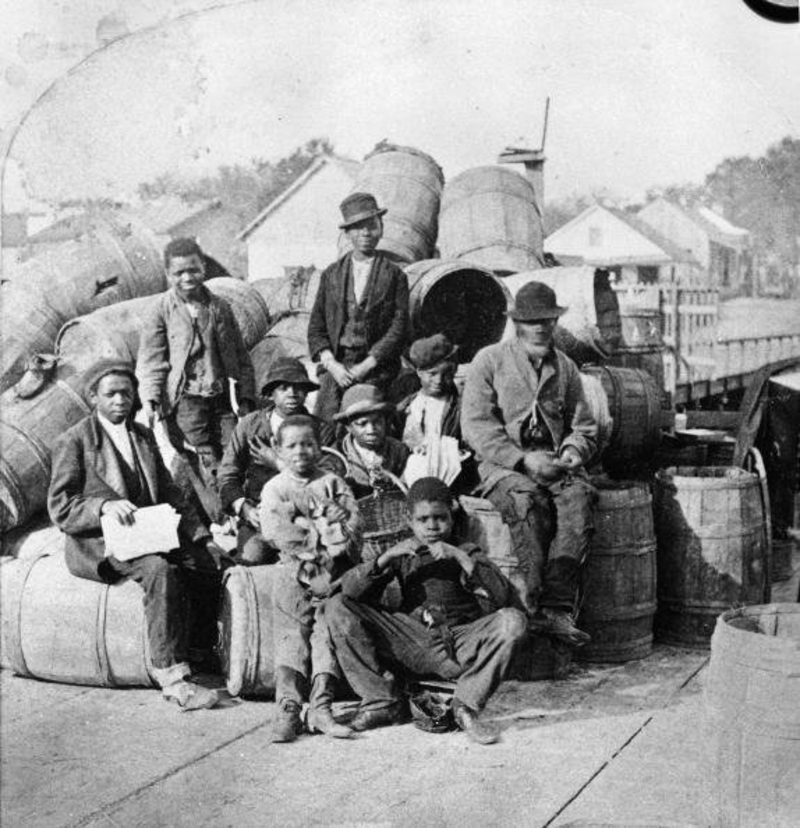

Whilst Jefferson kept detailed records and logged the lives of his hundreds of slaves, there were very few artefacts remaining. A scarce few individual photos of people from some of the families are all that are left at present. The descendants, and the curators of Monticello’s museum have since held several ventures which have revealed more remarkable information about these slaves. At last, justice to those who had seemingly lost their place in the history books.

The Hemings’ Family Tree

It seems that Sally’s name is not the only one to have made a significant contribution to the United States. Her family tree also includes a number of descendants who also held Jefferson’s genes. It is an impressive, wide-reaching lineage to follow which can be traced to the present day.

Historian Annette Gordon-Reed in 2008 published her book The Hemings’s of Monticello: An American Family, which provides wonderful insight to the lives of slaves at the time. Gordon-Reed views the slaves through a lens which is analytical; she recounts the history of generations of the Hemings family based on surviving legal records, diaries, farm logs, newspapers, archives, correspondences and even oral history. In the next slide we will find out the details of her extraordinary findings.

Life After Monticello

Madison Hemings, one of Sally’s daughters has said that her mother’s first child passed soon after her return from Paris with Jefferson. The records which Jefferson kept confirmed this story, and also added that Hemings had six children after her return to the U.S. Of the six, four survived into adulthood: Madison, Eston, Beverley and Harriet. With time, all, except for Madison made the choice to live amongst the white society in the North. Madison’s memoir is critical in furthering her mother’s story, and that of her siblings.

According to Madison, his sisters Beverley and Harriet both married affluent Washingtonians, and lived within DC’s white community. On the other hand, the Hemings brothers both married free women of colour in Virginia. Eston perhaps made the most surprising choice of all; changing his surname to Jefferson, to acknowledge the U.S President as his biological father.

An Influential Lineage

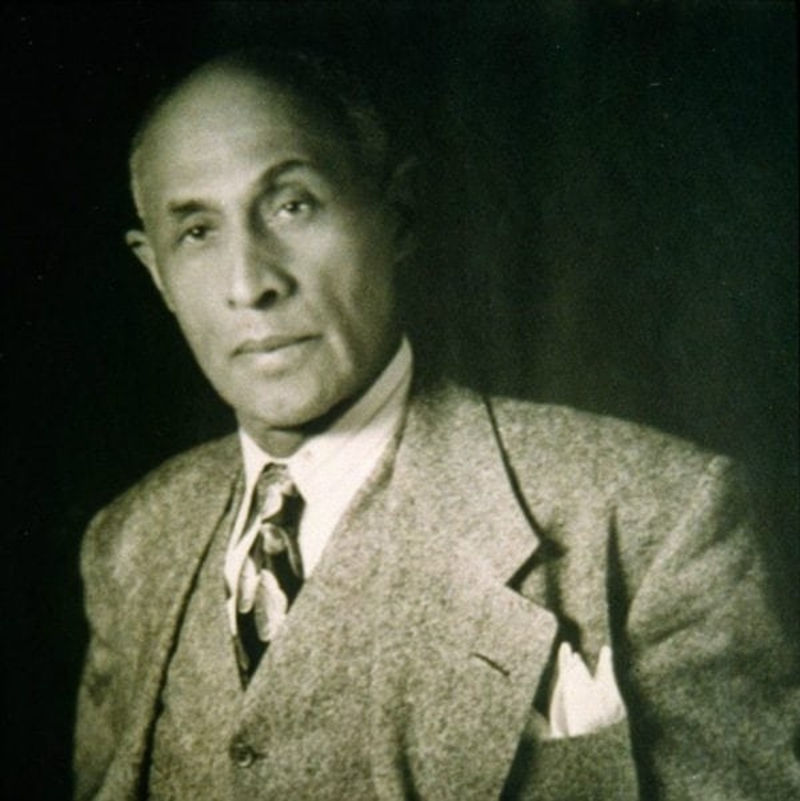

Hemings’ sons were to go on to enjoy success in adulthood, with multiple children taking up arms and fighting on the Union’s side in the bloody Civil War. Sally Hemings’ family tree expanded to include several grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who carried on the family legacy. It seems that politics was in the DNA of the offspring of Jefferson, with his and Hemings’ great-grandson, Frederick Madison Roberts becoming the first person elected – of black ancestry- to take up office on the West Coast of the United States.

He was to serve more than one term in office, serving for over 20 years in the California State Assembly. However, this was not all for the Jefferson-Hemings descendants.

Giving Voice

An effort in 1993 was made by Monticello historians to glean more information from the descendants of the enslaved at the estate. Over 200 interviews were conducted, with the goal to collect personal accounts of the African-American families who lived at Jefferson’s Virginia plantation, from their descendants. This oral history project was furthered in recent years, reaching a peak with a 2016 public summit titled “Memory, Mourning, Mobilization: Legacies of Slavery and Freedom in America.”

The summit opened with the following bold, chilling statement: “My ancestors were enslaved at Monticello. Generations of people bound to the earth, by blood and by law.” This gathering of people indicated just how many families had been impacted by the plantation, and in turn, by Thomas Jefferson. Finally, those who had been slaves were given a voice, to tell their story, albeit hundreds of years later.

Opening Up

Most importantly, is the adjustment in the narrative told to the general public. Curious about the scandal and mystery surrounding the expansive grounds of Monticello, the estate sees over half a million visitors. You’d want to hope all these people are told the most realistic version of events! The gradual shift now portrays a more holistic story, with the details of slaves which were once glossed over, now brought to light.

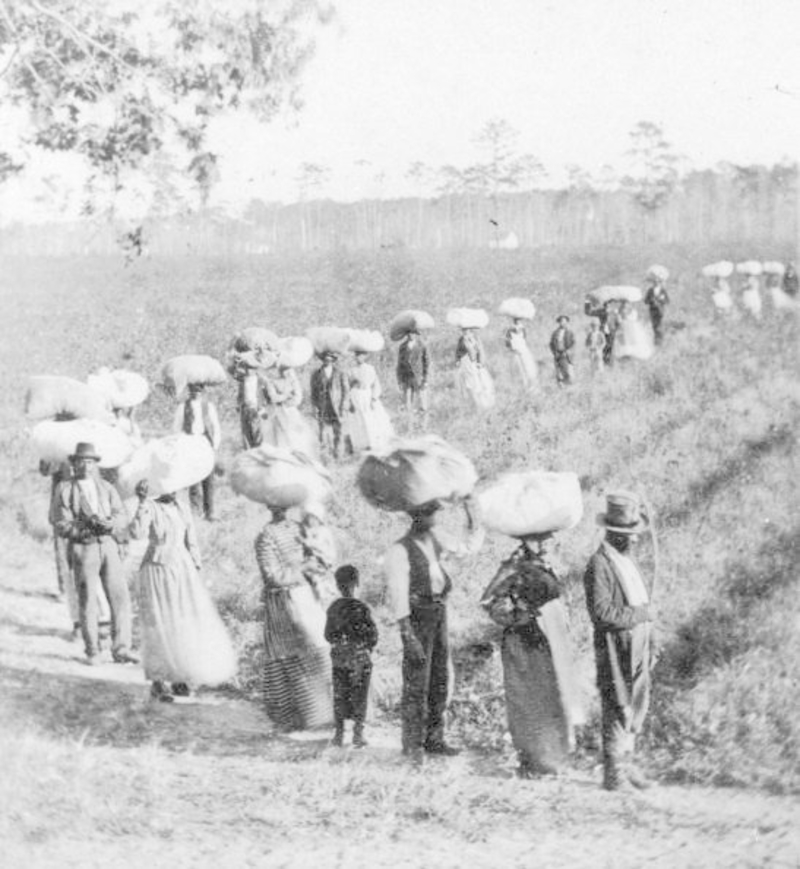

Tom Nash, one of the expert guides at Monticello made the candid remark to his visitors “this is a spectacular view from this mountaintop.”“But not for the enslaved people who worked these fields. This was a tough job and some of them – even young boys 10 to 16 years old – felt the whip.” Whilst these days Monticello is green pastures and sprawling lawns, it was not enjoyed in that way hundreds of years ago. Conditions for the enslaved were harsh, cruel even; these people were considered as sub-human, and whilst were perhaps afforded better living conditions than many slaves in the U.S., were still treated in a manner which was almost intolerable.

‘No Such Thing as a Good Slave Owner’

Nash, constantly in the firing line of the public’s probing questions shares some of the wide range which are thrown at him. “Why did some slaves want to pass for white when they were freed,” one tourist asked, while another questioned: “why did Jefferson own slaves and write that all men are created equal?” Retrospectively, Nash’s answer reflects the realities of the time, “working in the fields was not a happy time. There were long days on the plantation.” “Enslaved people worked from sun-up to sundown six days a week. There was no such thing as a good slave owner.”

It doesn’t get much clearer than that; any slave was still just that: a slave. The one thing these people yearned for, was something which was dangled in front of them yet not even remotely within their grasp; freedom. And the man who was supposedly able to grant them it, guarded his secret jealously.

Acknowledgment

July 2017 saw Monticello’s 55th annual Independence Day, and while the memory of its history may still linger in the minds of the descendants of the enslaved, a celebration was held. Not just to celebrate the estate, but the memory of those who had either experienced, or been touched by the events of the plantation. 70 people from 30 countries streamed in from all corners of the globe to attend the event, and in doing so, became naturalised citizens of the United States.

This acknowledgment brings together those affected, and unites them as a whole, to create a sense of belonging. The United States, and the world along with it continue to recognise the complexities of American history and are working harder than ever to acknowledge the contribution, and often, sacrifice of those who were not free as you or I am today.

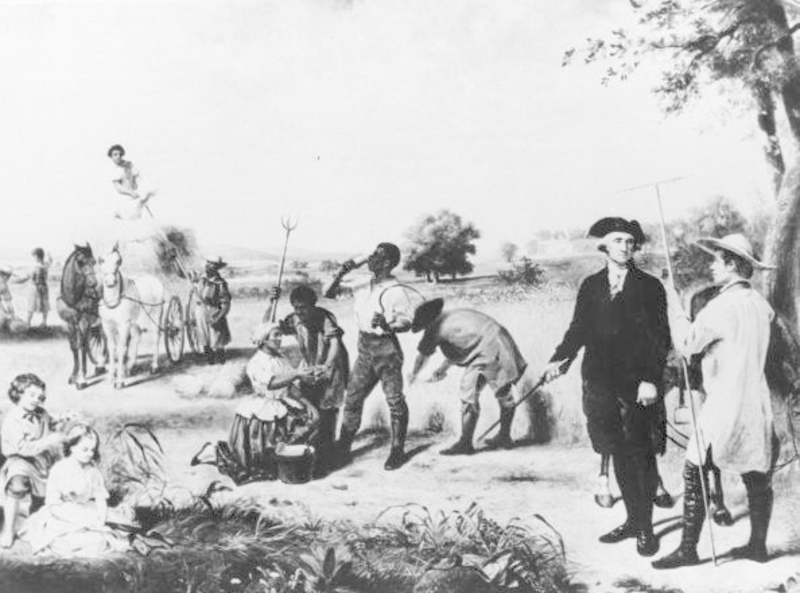

Jefferson Wasn’t the Only One

Whilst it is easy to point the finger at Jefferson as a leader who went back on his word of creating a freer, more equal America, he was not the only prominent U.S. figure with a history of slave ownership. As historians scour documentation and evidence of the impressive line-up of presidents, it has been found that twelve leaders of the United States were slave owners at a point in their lives.

Of those twelve, eight were slave owners whilst they held office! Despite the United States’ Declaration of Independence being founded on the principle of “all men are created equal” there was a glaring hole in this statement. The links of these Founding Fathers to participating in slave ownership highlight a fatal flaw in America’s history, presenting an astonishing contradiction which is forever ingrained in the nation’s past.

Early Years of the Republic

Although there were paradoxical and conflicting views on the institution of slavery, of the first five presidents of the United States, four were slave owners! A nation which was supposedly built on equality and freedom was indeed a huge lie, which tested the integrity of the nation and its leaders. The “father of the country,” George Washington, is among the four slaveowners. Over 300 slaves lived on the first President’s Mount Vernon plantation, and this number grew.

Despite his engagement of slaves, he was singular in the respect that he chose to free his personal slaves. When his will was read, it called for the freeing of the slaves upon his wife Martha’s death. However, Martha had more charity and goodness in her heart, and decided to free a large number of them earlier, releasing them only a year after he had passed away.

The Exceptions

Despite the occurrence of slave-holding presidents in the early years of the nation’s history, John Adams, the second President of the United States, proves an exception. He was the first resident of the White House, and whilst slave labourers did work to construct the iconic residence, Adams himself never owned slaves. He was considered as holding “moderate” views on slavery and decided to listen to the message of the Declaration of Independence.

Like his father before him, Adam’s son, John Quincy, the sixth U.S. President, also did not holds slaves during his lifetime. In his final years, and the years where he was not holding office, Adams sought to oppose the institution of slavery and spread the message of freedom for all regardless of race.

Presidents After Jefferson

Slave laborers were not merely used by Jefferson on his plantation as we have found, what with some working on Mount Vernon as well as the fabled White House. Though Jefferson once referred to slavery as an “assemblage of horrors,” he was not to be the last President to be a slave owner. James Madison, James Monroe and Andrew Jackson also participated in the institution, as well as eighth President Martin Van Buren.

These Presidents often noted they opposed the expansion of slavery yet could hardly be considered abolitionists; perhaps they enjoyed the benefits of owning slaves to further their prospects. Surprisingly, the last two Presidents to own slaves were both men associated with Abraham Lincoln. Let’s have a final look at who these men were!

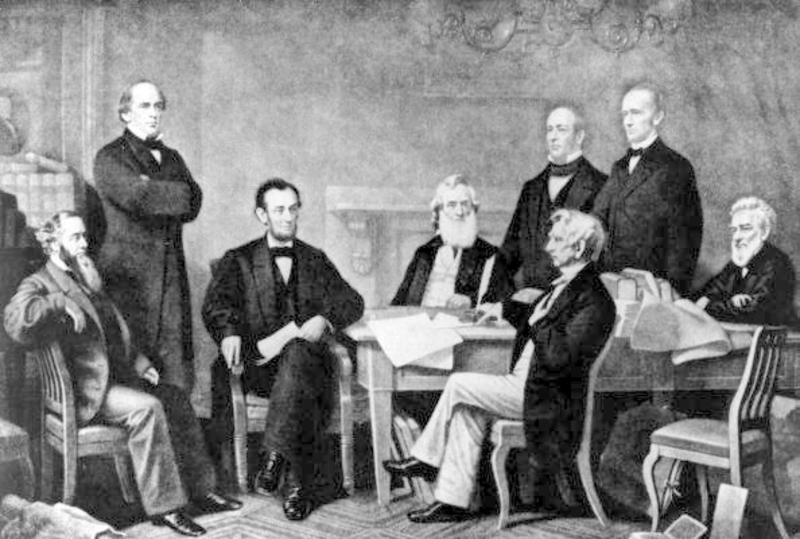

Before Lincoln

Before Lincoln, a number of other prominent figures held slaves during office, including; John Tyler, James Polk and Zachary Taylor. The last president to personally own slaves was Ulysses S. Grant. Serving two terms, between 1869 and 1877, the former general of the Union Army kept a single black slave named William Jones. However, even he granted him his freedom, noting later on that slavery was “a stain to the Union (that) people had once been bought and sold like cattle.” As was the fashion of the time, it was perfectly acceptable to own slaves. However, a growing movement, which had been given impetus by Abraham Lincoln, was sure to overturn this archaic institution.

Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation championed the passing of the 13th Amendment to end slavery. The bill was controversial at the time, and, Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s right-hand, who owned slaves, even lobbied against his own President! Finally, in 1863, the 16th U.S. President Lincoln freed almost 3 million enslaved people with his Emancipation Proclamation. America was officially abolished two years later, with the adoption of the famous 13th Amendment.